To all of my followers, I made a mistake on my posting number so I'm reposting this as Part 196.

Our piece on the Conflict Resolution Diagram is no quite ready to go to press, so in today’s posting I’m going to substitute what I think is an interesting and common place dilemma facing many manufacturing plants. I have been working with a client that produces medical devices and a couple of weeks ago I had an interesting discussion with the plant’s GM.

Our piece on the Conflict Resolution Diagram is no quite ready to go to press, so in today’s posting I’m going to substitute what I think is an interesting and common place dilemma facing many manufacturing plants. I have been working with a client that produces medical devices and a couple of weeks ago I had an interesting discussion with the plant’s GM.

I had done an assessment of

his plant earlier in the year and one of the most disturbing findings was the

level of work-in-process (WIP) inventory scattered throughout his plant. It was clear to me, after an in depth look at

his operations, that there was no synchronized flow in place. In fact the system in place was clearly based

upon the principles of “push” rather than “pull.” That is, keep the workers “busy” all of the

time. The plant was also characterized

by large batch sizes and no discernible production scheduling system to control

the level of WIP. Part of the discussion

I had with the GM was the impact these large batch sizes were having on the

overall production lead times which in some cases were as high as 6

months. This concept of batch size

versus lead time is the subject of this posting.

Before moving on, let’s

explore the differences between a synchronized and nonsynchronized manufacturing

environment. A nonsynchronized

environment is characterized by systems where products have long manufacturing

lead times and materials spend a large amount of time waiting in queues as WIP. Studies have demonstrated that in many

manufacturing plants, the majority of manufacturing lead time for materials is

actually spent waiting in these WIP queues.

In some plants, the actual processing time on a given order is as little

as 5 percent of total manufacturing lead time and this plant’s lead time

certainly met this scenario. Conversely,

synchronized manufacturing plants have relatively short manufacturing lead

times and materials spend very little time waiting in queues. Unlike the nonsynchronized plant, processing

of materials in a synchronized plant accounts for a relatively high percentage

of the manufacturing lead time.

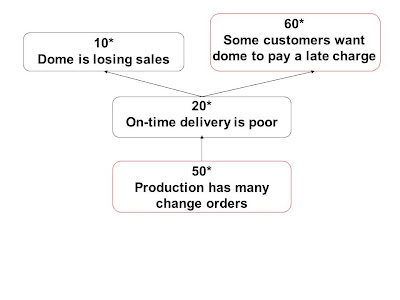

There are several key

factors that impact synchronization in a manufacturing setting, but one of them

in particular, batch size, plays a very large role. As I explained to the GM, improperly chosen

batch sizes contribute significantly to nonsynchronized material flows. The direct result of this lack of

synchronization are increased levels of inventory, extended manufacturing lead

times, poor on-time delivery and needless operating expense. Many times these plants must resort to

overtime and expedited freight charges. Of

course, this GM did not agree with and asked me to prove it to him. One of the easiest ways to demonstrate the

impact of batch sizing decisions on synchronized flow is by looking at a simple

example which is what we did.

In this process example

there are two side-by-side machines used to clean the interior of the

parts. The two different media types are

used to remove things like burrs or other obstructions/impediments from the

parts. The figure below summarizes the

normal running conditions for the parts entering this 2-step process. The parts to be processed are received from a

feeder process in batches of 48 parts and 8 parts are loaded into a fixture which

is inserted into the first machine.

These 8 parts are run for 30 minutes and then removed, cleaned and

placed in a holding rack. The next 8

parts are run and the process repeats itself until all 48 parts are

completed. When all 48 parts are

completed, they are then moved to the second machine (Media Type 2) which

contains a second media type where, like the first machine, are run in batches

of 8 parts. From beginning to end the

process takes a total of 360 minutes of elapsed time from beginning to end to

complete all 48 parts (i.e. 180 minutes on Media Type 1 machine plus 180

minutes on Media Type 2 machine). This

example assumes no setup time.

This is a classic example of

a nonsynchronized flow, but what would this same scenario look like if the flow

was synchronized?

This is a classic example of

a nonsynchronized flow, but what would this same scenario look like if the flow

was synchronized?

In the figure below we see

that instead of waiting for all 48 parts to be completed on the Media 1 machine,

after completing the first run of 8 parts, we immediately start processing the

parts on the Media 2 machine.

In this case our wait time

is the length of time to complete the first run of 8 parts or 30 minutes rather

than the 180 minutes of wait time in the nonsynchronized scenario. Now both machines are running simultaneously

until all 48 parts have been completed on both machines. Instead of taking 360 minutes to complete, as

in the unsynchronized flow, we see that the total elapsed time is now only 210

minutes. In effect what we have done is

change the transfer batch size from 48 parts to only 8 parts and the result was

an almost 60% reduction in lead time. It

didn’t cost us anything to achieve the seemingly impossible (impossible to the

GM that is).

In this case our wait time

is the length of time to complete the first run of 8 parts or 30 minutes rather

than the 180 minutes of wait time in the nonsynchronized scenario. Now both machines are running simultaneously

until all 48 parts have been completed on both machines. Instead of taking 360 minutes to complete, as

in the unsynchronized flow, we see that the total elapsed time is now only 210

minutes. In effect what we have done is

change the transfer batch size from 48 parts to only 8 parts and the result was

an almost 60% reduction in lead time. It

didn’t cost us anything to achieve the seemingly impossible (impossible to the

GM that is).

It should be apparent then

that one of the key considerations we should always be evaluating is the

concept of transfer batch sizes within a facility as part of our synchronized flow

process.

Bob Sproull